Big game hunting and the Snow Museum

This originally appeared in the Montclarion Dec. 7, 1999. Images courtesy of the Oakland History Room.

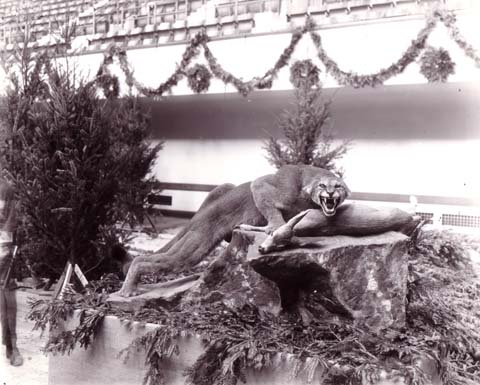

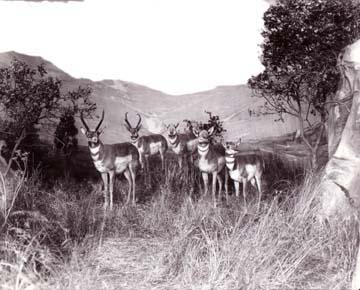

Today, Snow Park is a wonderful triangle of green space that provides respite to weary office workers, those hoping to improve their putting skills and anyone who enjoys the smell of cut grass after the industrial mowers do their job. Not too long ago, however, safari animals left the veldt with bullets in their hides and were resurrected here with sawdust innards in the Snow Museum.

The Snow Museum began in 1922, when big game hunter Henry Snow donated his massive collection of animal pelts and 50,000 bird eggs to the city, with the proviso that the city construct a fireproof museum to house them. Instead, the city turned over a 30-room mansion located on 19th Street between Harrison and Alice.

At first, no one came. Mayor Davies had to have a sign painted to let people know that a taxidermist’s dream was inside. Unfortunately, not all of the collection, valued at $2 million, could be displayed: the ceilings were not tall enough, for example, for the mounted giraffes. While two tons of materials were on display, 25 tons were in boxed storage.

Snow considered the three white rhinos the greatest treasure of the collection, since there was only one small band of white rhinos still roaming the planet. Apparently he missed the point that killing three of them made still less! The largest weighed 5,000 pounds with a 22-inch horn and was never exhibited because it was too large for the mansion’s rooms.

Snow’s exploits, one has to reluctantly admit, were very exciting.In 1923, he traveled to the Arctic and was charged by a Kodiak bear, which he dispatched with a bullet to the eye. Scrambling over an ice floe threatening to upend itself, he recovered the body of a felled walrus. He met Amundsen, discoverer of the South Pole, and found mastodon bones with 11-foot tusks. As if this trip wasn’t adventurous enough, his boat was almost crushed by ice.

Snow’s exploits, one has to reluctantly admit, were very exciting.In 1923, he traveled to the Arctic and was charged by a Kodiak bear, which he dispatched with a bullet to the eye. Scrambling over an ice floe threatening to upend itself, he recovered the body of a felled walrus. He met Amundsen, discoverer of the South Pole, and found mastodon bones with 11-foot tusks. As if this trip wasn’t adventurous enough, his boat was almost crushed by ice.

Snow’s son Sidney carried on the pith helmet tradition. In 1924, he also hit the Arctic and discovered the bodies of four frozen Canadian scientists who had been caught in a blizzard. Sidney Snow attempted to harpoon whales who (you’ll like this) fought back, nearly tipping over his vessel. An 1,800-pound polar bear captured by Sidney lost 300 pounds on the voyage down from the Arctic, which sounds hopefully like this bear was a live exhibit. Sidney also brought back two Eskimos who expressed great amazement at the size of San Francisco.

The fireproof facility promised by the city never came. In a huff, Snow threatened to donate the collection to San Francisco instead, although he preferred to keep the animals in Oakland. “I am for Oakland first, last and all the time,” he said.

(Civic pride was a beautiful thing in those days. Snow and his son had made motion picture films of their sojourns in Africa, and at a screening at the Hotel Oakland in 1922, crowds cheered the sight of the word “Oakland” imprinted on the side of a safari vehicle.)

In 1924, Snow and a corporation of businessmen raised $1 million and offered to lend it to the city to build the museum. The city attorney deemed such action illegal, although today it wouldn’t be—we might have had the Oakland Museum 50 years earlier! Architect Maury Diggs, who built the fabulous Fox Theater on Telegraph Avenue, went so far as to draw up plans for the proposed but never-built museum.

Snow had a lot of grand schemes. He wanted the city to dig a 40-foot-deep cave on the Lakeshore edge of Lake Merritt, which he would supply with lions, rhinos, hippos and “a giraffe or two.” The kicker was that there would be no bars to cage the animals: they would be curbed only by a water-filled moat that would be too wide for them to jump and too deep to negotiate. Needless to say, the idea didn’t get off the ground.

Snow had a lot of grand schemes. He wanted the city to dig a 40-foot-deep cave on the Lakeshore edge of Lake Merritt, which he would supply with lions, rhinos, hippos and “a giraffe or two.” The kicker was that there would be no bars to cage the animals: they would be curbed only by a water-filled moat that would be too wide for them to jump and too deep to negotiate. Needless to say, the idea didn’t get off the ground.

As part of the white rhinos’ revenge, Snow died in 1927 of Blackwater Fever, apparently contracted during his African expedition. The museum carried on under the curatorship of Snow’s daughter, Nydine Latham. Latham once said of the taxidermy collection, “I don’t feel as if (the animals) are dead because they have been so well preserved and can remain that way for ages if properly cared for.”

In 1961, the parcel had a close call. The Sheraton Hotel wanted to demolish the Snow Museum and build a 10-story, $7 million hotel. Back in 1922 when the museum was established, City Council had voted $140,000 to purchase the three adjoining lots so that a park would surround the museum. Luckily, the decision-makers in 1961 remembered the commitment to green space and the proposal died.

In 1967, the Snow Museum finally closed. By that time, stuffed animals had fallen into disfavor, and the collection was viewed as very dusty and dismal. Most of the creatures were auctioned off; perhaps your grandmother has a dik-dik in her garage. A few pieces were retained by the new Oakland Museum, which merged three museums: the first Oakland Museum at the Camron-Stanford House, the art gallery housed in the Oakland Auditorium, and the Snow Museum.

So the next time you sit in the lushness of Snow Park to eat your bag lunch, remember the beasts with bared fangs that soundlessly prowled their artificial habitats.

Pingback: Erika Mailman » Montclarion Columns