Güde is in trouble. She is starving, and a viciously-cold winter has descended on her medieval German village, scattering the game and birds so no one will eat. In these desperate times, her daughter-in-law needs a way to feed her children—and a way to vent her helpless anger.

Güde is in trouble. She is starving, and a viciously-cold winter has descended on her medieval German village, scattering the game and birds so no one will eat. In these desperate times, her daughter-in-law needs a way to feed her children—and a way to vent her helpless anger.

When she accuses Güde of witchcraft, the trouble only deepens… because Güde isn’t sure she’s innocent.

This novel follows Güde’s struggle for truth, to figure out the reality of her soul’s status, and to hang on to life until good times return to the village.

*The Witch’s Trinity was a San Francisco Chronicle Notable Book of 2007,

and a Bram Stoker Award finalist.*

Praise for The Witch’s Trinity:

“A well-constructed novel and a gripping, well-told story of faith and truth.”

—Khaled Hosseini, international bestselling author of The Kite Runner

“A linguistic enchantress has arrived among us, gifted in transmogrifying the mundanities of historical fiction into tableaux of indelible terror and abiding beauty.”

–James Morrow, author of The Last Witchfinder

“Evocative and engrossing…a frightening tale of both the weakness and strength of the human soul. I was gripped immediately by the story; it reminded me of Year of Wonders and I read it in nearly one sitting.”

-Robert Alexander, national bestselling author of The Kitchen Boy and Rasputin’s Daughter

“Powerful and thought-provoking, The Witch’s Trinity questions the nature of truth while bringing to vivid life the power men’s fear has over women’s lives. Haunting and unforgettable.”

-India Edghill, author of Wisdom’s Daughter

“Surprising and engrossing, The Witch’s Trinity draws you in and then keeps you gripped till the very last page.”

-Martin Davies, author of The Conjurer’s Bird

“The Witch’s Trinity is one of those mind-bending histories that make you wonder how many women in the 16th century hid in fear of being condemned for their healing powers. Erika Mailman superbly re-creates the terror of the women who lost, and the hope of those who managed to survive, the most egregious war of the sexes.”

-Holly Payne, author of The Virgin’s Knot and The Sound of Blue

“A Gothic horror story-starvation, superstition and persecution, if you believe in witches-this is a disturbing and compelling read.”

-Tobsha Learner, author of The Witch of Cologne

WRITING THE NOVEL:

I wrote The Witch’s Trinity after spending a lifetime thinking about the men and women accused of witchcraft in the Middle Ages. For some reason, I had been fascinated by witchcraft ever since I was a child.

Once I sat down to write, something astonishing happened: my mother told me we were related to an accused witch, Mary Bliss Parsons. This news came by email, no less, and I’ve mulled quite a bit over the oddity of such old news (my ancestor was first accused in 1656) coming to me via such new technology. My mom sent a link to the UMass website on Mary Bliss Parsons, which is well worth clicking over to (but then return, please!)

This site contains all the extant testimony from Mary’s first case, and the indictment from the second. Yes… she faced trial twice. The most amazing thing is looking at the scanned-in handwritten documents prepared by the court clerk—that old-timey writing where S’s look like F’s, and they use very strange abbreviations, like “yt” standing for “that.”

Luckily, my ancestor was acquitted both times and died of old age. The Witch’s Trinity has an Afterword about her story.

But the novel is about a fictional woman Güde. I first thought of her as I listened to a history professor’s lectures about the statistical phenomenon of daughters-in-law accusing their husband’s mothers of witchcraft…because they were starving, and wanted to rid the family of an older, useless member. As I so often do when I hear stories of atrocity, I think not of numbers, but of one solitary, specific person.

The witch craze in Europe qualifies as a holocaust. Women (and men) were executed during a 400-year period. Can you imagine, four hundred years of such incredible ignorance and downright foolishness? The United States celebrated its bicentennial when I was a child, so if we applied Europe’s madness to our history, we would still be killing witches until the year 2176.

I crafted Güde from thin air to demonstrate the Everywoman of these horrible times. Like most real accused witches, she is older, she is somewhat unstable mentally, and she is a burden to her family.

One of the saddest parts of my witchcraft research has been learning that we haven’t left this fear behind in the dungeons-now-museums of Europe and New England. Today witchcraft persecutions continue in modern-day African countries such as Congo, Congo Republic, Angola and Zimbabwe, to name a few where I have heard specific accounts emanating from. At my blog, I write about these witchcraft reports in the hope that increased awareness can make a difference.

If you have already read The Witch’s Trinity, you know about the Malleus Maleficarum, the famous witch hunting Bible from medieval Germany. It is no authorly fabrication, sadly. The book exists, and was responsible for fanning the frenzied flames of witchcraft fears. I also blog excerpts from it.

Q&A with Erika Mailman

Q: What inspired you to write The Witch’s Trinity?

I was driving my car, listening to an audiotaped lecture series called “The Terror of History” by UCLA history professor Teo Ruiz. Ruiz said something that just blew my mind: that sometimes family members accused other members of witchcraft because they were so hungry.

I thought, “What kind of hell does your life have to be, that you will offer up a family member so that there is one less plate upon the table?” I was appalled and shaken at this very different interpretation of the word “family.” (But then again, medieval people felt very differently about all kinds of relationships; infanticide was commonplace.)

I kept mulling this horrifying idea over. And then I hit on a plot element that I thought could help me write a novel: what if a woman were accused of witchcraft, but suffered from senile dementia and therefore didn’t know whether she was a witch?

I hunkered down with many books, including Jeffrey Burton Russell’s Witchcraft in the Middle Ages, to do as much research as I could. I was more writer than historian, I fear. However, much of what is included is truthful, but I have taken some liberties – for example, I found reference to a pebble test like Künne undergoes, but altered it from one pebble to three, to draw the comparison to the holy trinity.

Q: The scenes of dancing at the festivals showed how happy this fictional village once was. What made you include that?

I was for a brief, wonderful time a member of the Schulplattler group, a German folk dance group in Oakland, California. Many of our dances date to medieval times, such as the Maypole Dance and the Miller’s Dance. Learning how to move my body in these ancient rhythms and patterns, aided by flying sweat and exuberance, felt like putting the needle down into the groove of an LP. It was a way to learn, to feel in the gut the simple earthy pleasures of Güde’s life.

Q: On the other side of the coin, this book unflintingly shows the horrors faced by those who were accused. What was it like to research such horrid history?

When I wrote scenes where women were harmed, I felt a sickness in the pit of my stomach. As much as I was reveling in the maniacal bloodthirsty way writers do when they actually manage to put their characters in trouble, I couldn’t escape the little voice in the back of my head that was saying: This isn’t fiction. This was the story of many women’s lives.

Several years ago, I visited Amnesty International’s touring Torture exhibit in San Francisco. I was humbled by the true, real, sordid pain that humans inflict on each other. Too often, I’d wince when bending down to read a placard, to learn that the medieval device I’d just been looking at was still in use today.

Q: Your ancestor was accused of witchcraft–what’s the story behind that?

My 11-greats grandmother Mary Bliss Parsons was accused in 1656 Massachusetts, and again 18 years later. Both times, the courts set her free. She was accused of oddities like being able to step into the brook and come out dry . . . and huge crimes like the deaths of others. I learned about her while I was writing my novel . . . by an email from my mother! Such uncanny timing, to find this out while I was in the midst of writing about witchcraft. And also strangely dissonant to discover events that happened 250 years ago, via technology so comparatively new.

My mother sent me to a website on Mary–there are many, but click here for the one that includes a thoughtful analysis of her circumstances versus those of her main accuser. The website also has scanned-in transcripts: it was chilling to read the quill pen text a clerk scratched as my ancestor fought for her life.

I wrote an extensive Afterword on Mary Bliss Parsons that appears at the end of the novel. I also dedicated the book to her . . . I felt closer to her after exploring, by writing in the first person, the terrors she must have gone through.

Q: Why did you set the novel in Germany? Your ancestor was accused in New England.

The decision to set this novel in Germany just felt instinctual. I am of German heritage and, growing up in Vermont, I knew how much atmosphere mere snow can convey simply by being there. I wanted to create a world that was insular, bitingly cold and remote, wanted to offer the frightening thought that snow can effectively hide things.When I pictured Güde’s village, I saw the bleak slumped huts of Brueghel’s The Hunters in the Snow (yes, it portrays Holland but near enough to Germany to be meaningful). And as I said above, I didn’t know about my ancestor when I started writing the book.

Q: What is the Malleus Maleficarum?

The Malleus Maleficarum (The Witch’s Hammer) is a witch hunting bible written by two German friars in the late 1400s. They traveled the countryside ferreting out witches, under the aegis of Pope Innocent VIII. Later, they collected their “wisdom” in a volume that was printed and distributed in huge numbers, a bestseller of its day that went into repeated editions. In fact, you can still buy it today.

In my novel, the friar that comes to Tierkinddorf is armed with the Malleus, and it guides his attack upon Güde. Each chapter begins with a quotation from the Malleus. If you are interested in more on the Malleus, you can click here. I also frequently blog with excerpts from the Malleus; click here for my blog.

Q: Where can I learn more about witchcraft?

Since my book is a novel, it’s not intended to be a resource for anyone researching European witchcraft. It may offer a useful amalgam of information for those who are unaware that women perished in a 400-year cycle of suspicion and hatred. My hope is that it might inspire readers to do their own searching. Here are some of the books or other sources I relied on while researching.

Jeffrey Burton Russell’s Witchcraft in the Middle Ages

John Putnam Demos’ Entertaining Satan

Teofilo Ruiz’s Terror of History audiotaped lectures

The Malleus Maleficarum

Read the San Francisco Chronicle review here.

Read Erika’s Chicago Tribune op-ed on witchcraft here.

Reading Group Questions for The Witch’s Trinity

Please be aware that these questions may constitute plot spoilers!

- Do you think Irmeltrud truly believed her mother-in-law was a witch, or was Güde correct that she wanted fewer mouths at the table?

- The Christian faith reveres the Holy Trinity. What does the title The Witch’s Trinity refer to? Does the concept of trinity appear more than once?

- The Malleus Maleficarum is an actual book written by two Dominican friars in the 1480s. Discuss how it figures in this book. How do the quotes that begin each chapter relate to the specific content of that chapter?

- This novel pits Paganism against Christianity, yet both faiths lead the village to violence. What might’ve happened if the friar never visited Tierkinddorf?

- Describe Jost’s behavior. Does he adequately protect his mother, and the old family friend Künne?

- If you were Güde, imprisoned with Irmeltrud, would you share the Pillen with her?

- Güde makes the decision to confess to witchcraft, and even fingers Herr Kueper. Why does she do this? If you were she, would you ever confess, knowing that torture awaits those who refuse to do so?

- Güde achieves an uneasy civility with the villagers of Tierkinddorf, yet there are certain places she won’t visit. What are those places, and why? Was the stained glass window enough to purge the village’s guilt and heal the rift? What does the window mean to Güde?

- Why does Alke choose to live with Güde, and why does Matern stay with his parents?

- Like The Turn of the Screw, this novel balances seemingly supernatural events with a narrator who questions her sanity regarding those occurrences. In the end, what do you think truly happened? Did the witches give Güde meat in the forest? Did she fly to visit her son? Was the cat a supernatural being? What conclusion does Güde herself reach?

- Do you think the friar truly misogynistic, or simply blindly adherent to his faith? Did he deserve his fate?

- The western world abandoned witchcraft trials thanks to the rise of the Enlightenment and other factors, but witchcraft persecutions continue in certain parts of the world today. Why do you think the belief persists?

BOOK JACKETS GALORE

Do you love thinking about cover art as much as I do? I spend a lot of time in bookstores thinking about what I like, what compells me. There were several designs used (and not used) for The Witch’s Trinity, and I’ll share them below. I’d like to hear what you think!

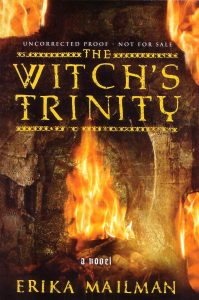

This was intended to be the hardcover book jacket. I adored it, but it was scrapped:

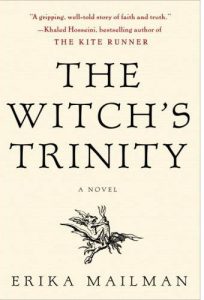

This is what was used for the hardcover instead:

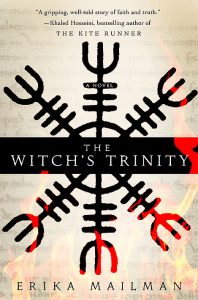

This is what might’ve been the paperback cover, but was not selected. I just saw this a few months ago (2017–the book went into paperback in 2008, so basically a decade later!) and blogged about the experience here.

And this is the image that was used for the paperback:

Here’s the lovely hardcover used in England:

And England’s paperback (slightly different: no woman!) and I like the way the page now looked aged and less glowing.

There was also an audiobook produced in England by Isis but I can’t track down the cover image. I wish this book would sell in more territories so I can see more beautiful jacket art! I’m absolutely fascinated by it.

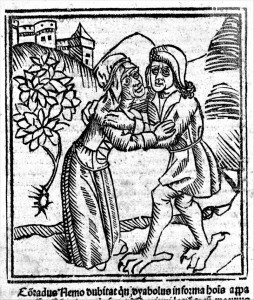

One last image: the endpapers for the hardcover were taken from the original Malleus Maleficarum. I loved that detail:

The Malleus Maleficarum cover. A “ghosting” of this was used for the end papers for the hardcover version of The Witch’s Trinity.

Oh, who am I kidding? Here’s one more image.